Last month, I tried one of those fancy weighing machines at my friend’s house – which measure much more than just your weight – and was shocked to discover the reading – the machine told me my ‘metabolic age’ was over 40, when I was just in my early thirties! (Compare this to my friend – whose metabolic age turned out to be in her late twenties, despite being the same age as me.)

Now, I’ve been hearing the term ‘metabolic age’ being tossed around in conversations, especially on my Instagram feed, without really knowing what it means. But this was a rude awakening – it was high time I delved deeper into what it meant.

Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) & metabolic age: what’s the connection

As I did more research, I realized that metabolic age is calculated on one primary metric: the Basal Metabolic rate or BMR. Your BMR is the number of calories your body needs to perform basic functions like breathing, absorbing nutrients from food and converting them into energy (metabolism), maintaining blood circulation, etc.

There are several factors that influence BMR – primary among them is your age. With age, our metabolic rate starts to drop, which then lowers BMR. Why? Because as we grow older, we tend to become less active, leading to fewer calories burnt during the day; we tend to lose more muscle (an average adult loses around 7-8% of their muscle mass every decade after thirty); and our nerve impulses tend to slow down.

There are a number of other factors that affect BMR besides age – such as gender and your body composition (how much fat-free mass you have, for example – which is your body weight minus your body fat).

Here’s a quick calculation that’s often used for calculating BMR, if you want to try it out:

Male: 66.5 + (13.75 x kg) + (5.003 x cm) – (6.775 x age)

Female: 655.1 + (9.563 x kg) + (1.850 x cm) – (4.676 x age)

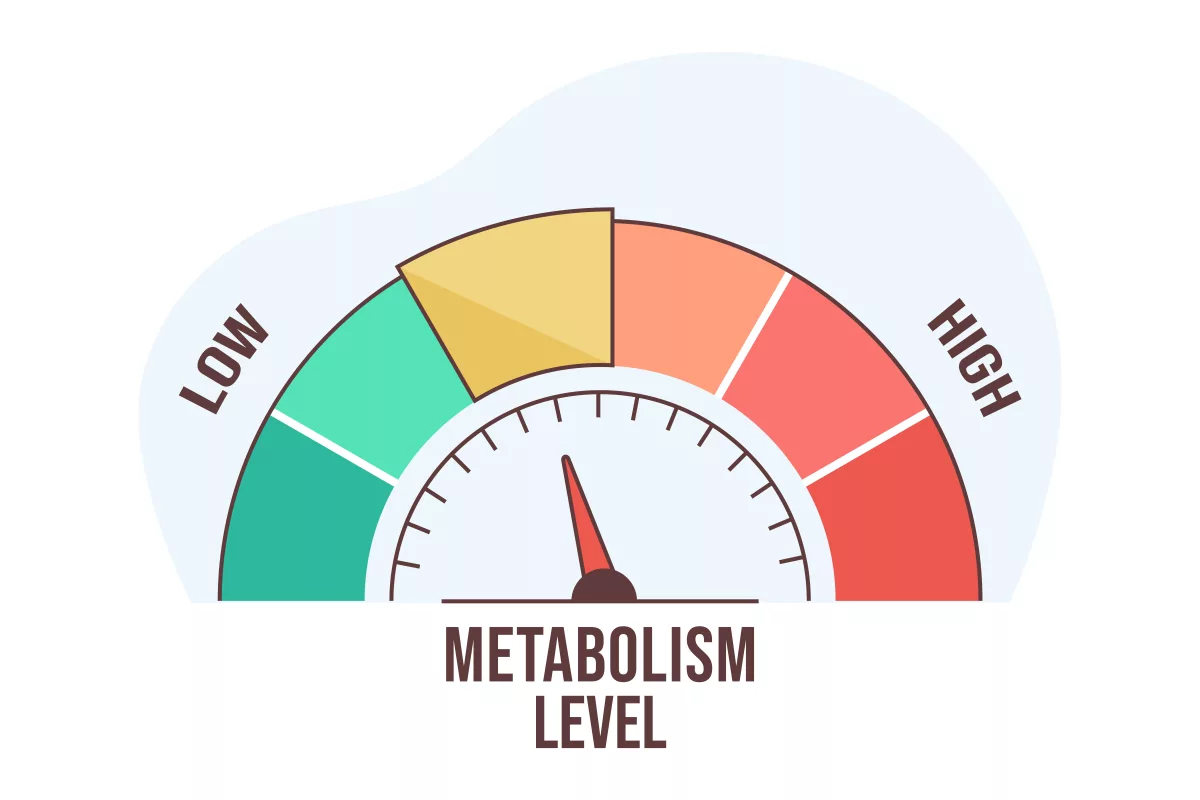

Metabolic age is the measure of your BMR compared to others in your age group. The higher your BMR, the lower your metabolic age. Simply put, it’s a scorecard – and at over 40, my BMR was equivalent to those significantly older than me rather than those in my chronological age group.

BMR, TDEE and RMR – what’s the difference?

There were two other terms I came across in my research. The first was TDEE – or the Total Daily Energy Expenditure. Your BMR is not the number of calories you need in a day – it’s only the basic minimum amount of calories your body needs to function. TDEE can give you a good idea of the number of calories you need in a day. TDEE is calculated by multiplying your BMR with an activity level factor (that is, how active you are through your day. For example, for me at my desk job, the activity factor is very low as compared to someone who does moderate exercise 4-5 times a week).

The other term I came across was resting metabolic rate (RMR). Although BMR and RMR are calculated differently, the difference between them is negligible – and the terms are often used interchangeably.

So what does having a higher metabolic age actually mean?

Generally speaking, a lower metabolic age than your chronological age is an indicator of overall good health. It implies a more efficient metabolism, typically associated with better health, better body composition (muscle v/s fat ratio in the body), lower blood pressure, general energy levels – the works. If your metabolic age is lower than your chronological age, On the other hand, a higher metabolic age suggests your body might not be as healthy as it could be for someone of your chronological age.

How is metabolic age calculated?

Calculating metabolic age can be somewhat tricky. There are several calculators online and on fitness apps that give you your ‘metabolic age’ – like the fancy weighing machine I tried at my friend’s. These usually estimate your metabolic age based on your BMR and personal data such as height, weight, and age. But while these calculators provide a quick and easy way to gauge your metabolic health, they give estimated values.

If you’re looking for complete accuracy, it might be harder to nail down. The latest research around metabolic age calculated the metabolic age of its participants by developing a special software to measure it over a 5-day period – and took into account participants body composition, resting blood pressure, waist circumference and a number of other factors. Plus, since metabolic age is a relative number – you need data of people in your age bracket with similar ethnographic factors – to get a true picture of metabolic age.

Of course, since I had none of this at my disposal, I decided to get an indirect calorimetry test done to accurately estimate my BMR – which was the key indicator for metabolic age. There are two ways to measure BMR: direct and indirect calorimetry tests. Direct calorimetry is a method in which you spend time in a controlled room with little to no movement. While this is accurate, it’s obviously not for general use. Indirect calorimetry is when you use a device to measure the If you’re looking for the most accurate number, then you’ll want to visit a clinic that offers direct or indirect calorimetry. This process involves using a device to measure oxygen intake and carbon dioxide output to assess the calorie burning efficiency of your body. The results were in line with my first assessment – I needed to up my metabolic age game!

Improving metabolic age

Now that I had made up my mind about improving my metabolic age – I dug deeper into the how of it. I realized that I had to combat the natural slowdown of my metabolism with age (that begins to happen in your mid-thirties).

Simply losing weight – and I admit, I have a few extra kgs – was not enough, because if you restrict calories, your body goes into starvation mode and slows down your metabolism, instead of increasing it. The trick was to add in exercise, while making changes to your diet and being at a caloric deficit – so that my muscle mass could improve and my fat levels went down – increasing my overall BMR.

So here’s what I tried:

I added HITT & strength training to my routine

Building muscle mass is a big factor to improving metabolic age. Muscles are more metabolically active than fat – that is, your body uses more energy to work muscles, which is why a higher muscle composition leads to a higher BMR, and a lower metabolic rate. While cardio (in the form of walking) was something I was fairly regular with, I started adding in high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and lifting weights to my routine, both of which helps build muscle mass. (I would recommend checking in with your trainer first – especially if you haven’t done HIIT before.)

I upped my protein intake

Protein intake supports muscle growth – especially when you couple it with strength training. Plus protein ranks the highest in the thermic effect of food (TEF) – that is, the number of calories your body uses to break it down, which further helps in boosting BMR and lowering metabolic age. I made sure to increase the quantities of lean cuts of meat, eggs, fish and legumes in my diet.

I made sure to get more sleep

I had read that getting a good night’s sleep has an important role to play in your metabolism levels, and inadequate sleep can also lead to weight gain. To combat that I started tracking my sleep meticulously and made sure to get around 8 hours every day.

I incorporated more water and tea in my diet

Incredibly, increasing your water intake can actually increase your body’s calorie consumption – studies have shown that drinking 500 ml of water increased metabolic rate by 30% for around 30-40 minutes. In fact, drinking around 2.5 litres of water a day could lead to a significant amount of resting calorie loss – and it might be even greater if you drink cold water! I also read that green tea and oolong tea could also lead to minor boosts in metabolism – and hey, who doesn’t love a nice cup of tea? These were both minimal things that I could very easily incorporate in my diet.

Takeaway

Overall, a couple of months into making these shifts in my diet and exercise, I started noticing improvements. I had significantly better energy levels, lost a couple of kilos, and found that, overall, eating better and exercising more regularly improved my mood. Was my metabolic age better than my friend’s yet? No. But was it better than before? Certainly.

The important thing to remember is that your metabolic age is not the ‘gold star’ of your fitness levels – it’s still a fairly new marker and research is ongoing on it. But treated in cohesion with other fitness markers – it can be a good guide to determine some underlying metabolic issues of your body.

Share this article